Paragliding (PG) equipment – typical setup

Introduction

Southwest Airsports sells everything a pilot needs to fly a paraglider safely. Investing in the best equipment is wise not just because it works better and lasts longer but because it increases our margin of safety. We are dealers for Ozone paragliders and harnesses as well as Sol and Sup'Air harnesses but can supply other brands, if necessary. We stick with Ozone because they are the Number One manufacturer in the world and have shared patents with other manufacturers that have greatly increased the safety of paragliding. We know their gliders well and it helps us equip students with the right gear.

Total cost for a typical PG setup is hard to estimate because of rampant inflation in the U.S. As of 2025 we can safely estimate that the overall cost will be less than $10,000 USD.

The wing

Gliders are rated for their ability to passively recover from collapses while flying. Gliders that have an EN "A" rating have a greater ability to recover spontaneously from collapses. Gliders with higher EN ratings require more pilot input to recover but have a higher top speed because of reduced drag. It is a potentially hazardous trade-off and why more instructors, especially those in the EU, recommend that pilots who fly less than 40 hours a year stick with "A" class wings.

Collapses can occur when flying in air that has turbulence caused by powerful thermals. These are usually present during summer midday conditions. "A" class gliders have more passive ability to recover than the higher class gliders. Which glider is best depends on what kind of air the pilot flies in. Optimally, pilots can have gliders for easy, calm, late-in-the-day air and gliders for active air. When in doubt go with an "A" class glider. Some of the time a pilot might wish he had a higher class better performing glider but when an unexpected collapse occurs near the terrain, for example, an "A" class glider requires the least input to correct the problem.

In the photo below, each cloud is the top of a thermal – this was an outstanding day for paragliding. The pilot in the photo below was the first ever to be towed up and thermal away to cloud base. Flying early or late in the day minimizes turbulence but flights will be shorter. With modern gliders the significant difference between them has become speed rather than glide.

What class of wing should a pilot fly? It depends on what kind of air he wishes to fly in and whether flying cross-country is important. Pilots who only fly on the coasts or ridge soar early or late in the day will rarely experience turbulent air. In such conditions, glider class is not important. On the other hand, pilots who fly midday during the hot times of the year may experience very turbulent air and must have the skills to react to unexpected events, especially if they are flying a more advanced glider.

The harness

It is much like sitting in an easy chair. The small red handle in the lower right in the photo below is used to deploy the reserve parachute stored under the seat of the harness. The paraglider is attached to the two karabiners in the upper center. The back of the harness contains stiff foam used to protect the back of the pilot in case of a fall. Modern harnesses also usually have an airbag for increased protection.

There is also a large zippered storage area along the back of the harness for stowing gear, like the glider packing bag and personal gear.

The pilot is securely strapped into the harness – he cannot fall out. When on the ground, the pilot is able to stand up easily though it is somewhat difficult to run with a harness attached. Once in the air, many harnesses have a foot strap attached so that the pilot can easily place himself firmly in the harness without letting go of the controls – the brakes. Some harnesses have the pilot almost in a reclining position while some are very upright. Some are shaped like a pod. These harness are the most comfortable and allow the pilot to be less exposed to the colder air of high altitudes. They are also the most expensive and used mostly by serious cross country pilots. The least expensive harnesses are little more than a series of straps and have no protection which makes them hazardous to use in the event of a rough landing.

The helmet

Many pilots prefer helmets with a faceguard that protects the face in case of an accident. The Charly Insider (photo here) is made of Kevlar and is specifically designed and certified to meet the strict standards of the European Union for air sports. How much is your head worth if you go bonk? This should not be a difficult question but it is for too many pilots. Helmets without faceguards should only be used by experienced pilots. Accidents at launch by new pilots tend to involve face plants which is why the faceguard is highly recommended.

The helmet in this photo (a Charly Insider) saved a pilot from certain death when he hit the ground after experiencing an unrecoverable collapse while flying XC in very strong conditions. He threw his reserve but it was *not attached* to his harness. There are many reasons why new pilots should have their gear checked by a competent certified instructor! This pilot was fortunate.

The reserve

Most pilots fly with a reserve in case they experience an unrecoverable collapse of their glider. Standard reserves (non-steerable) are a last resort because once under the reserve the pilot has no control over where he may land. Therefore, deploying a reserve when things go awry with your glider is always dicey. (Here is a video of the unexpected results that can happen during a deployment.) It is best to never be in a situation where reserve deployment might be necessary and why proper training is essential.

Steerable reserves are available for additional cost but they add risk because they can become tangled in the glider. Informational videos of steerable of reserves being deployed are not typical of what happens when a pilot must deploy. Getting tangled up in the glider following a collapse happens way too often (as once happened to yours truly). In these conditions, a steerable reserve may fail to deploy properly. This problem can be avoided by carrying a second standard reserve. It should be a warning to all that competition pilots are sometimes required to carry a second reserve because of deployment problems.

Experienced pilots may fly with special (and expensive) carabiners that can release the glider while it is loaded and stop the possibility of the glider causing problems after a reserve deployment. Therefore, it is always wiser to fly with plenty of altitude and do everything possible to fix the problem with your glider before reaching for the reserve.

If you fly with a reserve, purchase the biggest one you can carry. High Energy Sports makes a reserve that has unique aerodynamic properties which slow down the pilot's descent through the air. Sup'Air makes reserves that are very light. Here is some more info on reserve systems.

Yours truly has not yet thrown his reserve because the first priority is not flying in air where this may occur.

Below is the May Day standard reserve by APCO Aviation.

Footwear

The most common injury in paragliding is to the ankles. It is important to protect them AND why high top boots are recommended. Boots should not have lacing clips attached as they can snag the lines in and around the harness. You will probably never have a problem if you fly with boots that have open lacing clips. But why complicate a series of cascading events with lines snagged to your boots? A student of ours who knew better got his feet tangled together while trying to land – he was fortunate he didn't get hurt. Duct tape can be used to cover up boot hooks, if they are present.

The boots pictured below are made by Crispi of Italy – among the finest on the market. Yours truly has owned a pair for 15 years and have proven extremely durable, even when used for hiking. They are the most comfortable boots you can buy. They have sturdy vertical inserts which help prevent ankle injuries and are lightweight. The boots also do not have any exposed metal parts that might snag a glider line. Unfortunately, ordering the CRISPI boots can be challenging in the U.S.

There are other boots similar to the CRISPI's, such as the German HanWag.

Unfortunately, American tort law has made many ultralight products, including wings, engines, and boots risky to sell in sue-happy America. Ordinary hiking boots will also do but if you have weak ankles or want maximum protection for your feet, these types of boots are worth the investment. They are also good for cold weather.

The radio

The radio is far more than a convenience when flying. It is your connection with other pilots and the ground for weather information, pilots in distress, and emergencies and must be simple and easy to operate.

All USHPA pilots have the privilege of their own set of radio frequencies issued by the FCC in the 150 MHz range. 2 meter Amateur Radio Service transceivers can be modified to work on these frequencies. It is technically against the FCC rules to use these modified radios but the authorities have been looking the other way for decades and that is unlikely to change. If the FCC wanted to, they could immediately require that these radios (which are all imported) have a non-modifiable chipset. The "legal" radios are heavy and expensive ($1,000+) and do not easily work with accessories necessary for flying, such as push to talk systems and most communication systems found on the market.

There is cheap radio made in China called the Bao Feng which costs a fraction of the Japanese radios. It does not need modification and is ready to go. However, the receiver has poor selectivity and miserable sensitivity. Translated: nearby and powerful radio transmitters (commercial) can interfere with its operation. It does not work well beyond a few hundred yards unless high power is used which quickly drains the battery. It is also not particularly reliable and can be buggy to operate. We use them at our school but only for ground communication when training.

As a matter of safety, it is better in the long run to go with the more expensive radios, such as the YAESU, ICOM, or KENWOOD. Go to this page for detailed information and setup up of the most popular radios including the Bao Feng.

Southwest Airsports sells professionally modified radios that are pre-programmed and ready to go.

Compass

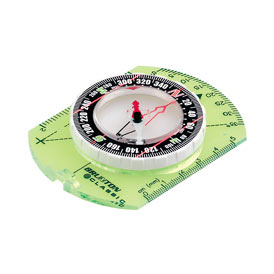

In case a pilot flies into a cloud by accident, a compass can greatly help because it instantly tells us our heading unlike a GPS. That is, we can head to the edge of the cloud and out rather than fly deeper into it.

Those who have sailed a yacht in fog know what this means. A GPS is next to useless unless a course is held steady for 5 or 10 seconds. Do NOT use a cheap bubble compass as they go everywhere if you are in turbulence. Do NOT mount the compass next to a GPS as the magnetic field in the GPS will affect the compass and vice versa. Here is a quality Brunton compass:

Handheld GPS, variometer, satellite communicator, combination unit

If you want to thermal well, especially in weak conditions, a variometer is the minimal tool. The variometer (or vario) measures your vertical speed through the air instantaneously. It gives an easy visual indication as well as a varying tone. It can even give an audio tone indicating when the pilot is in sink. The vario also can tell you your relative altitude, your actual altitude, air temperature, and airspeed. A recording variometer records everything from your flight. You can then download the data to your computer and analyze how you did. Only a recording variometer can give you the details.

"Am I drifting backwards over the top of the mountain and into danger?" It is very difficult to tell our speed and direction over the ground if we are a mile or two over it. With a GPS we can tell whether we are starting to slow down and in what direction we are going. In addition, if we ever get in trouble with the authorities per "you were flying over X" but we were not, the GPS log can be helpful.

Below is a photo of the Flytec Element Speed variometer ONLY. Many pilots fly with a combination variometer and GPS. Having a GPS integrated with the variometer is a handy feature, especially for those who fly in competitions. Both Flytec and Flymaster offer these combination units. 2024 Cost: $99 - $1,400 (cost is based on the functions desired, size, display, flight maps, and a built-in GPS). A typical recording variometer like the Element Speed that is easy to read costs about $ 450.)

The most common, rugged, and easy to use GPS in the entire world is the Garmin 64 series.

There are newer models of this GPS with features that are not that useful for ultralight pilots. Hands down, these GPS receivers are the most reliable and rugged on the market. I always carry one as a backup. In over 15 years, I have never had a problem with the Garmin. If you go in the water, even saltwater, they will still function. This is important if you fly in remote places, have a water landing, get your gear to shore, dry things out, and want to continue your journey. Combo units will not survive a dunking. Cost: $200 - $1,000. Used units can be a bargain.

For those who want help with thermalling or to compete, the sky is the limit on what you can spend e.g., the Oudie and other devices that are not only have a GPS receiver and a variometer but can connect to the cell system and other pilots. However, these combinations units are all subject to single-point-of-failure and why pilots should consider having (2) independent GPS receivers.

For safety and emergency use, the Garmin InReach Explorer + combines a GPS with 2-way satellite communications. One-way communicators, like the SPOT, are useful for tracking but should not be used if the primary purpose is for safety and emergencies. This is because the SPOT does not have 100% reliable communications between the satellite and recipients. Note: Long experience with the SPOT in-out-of-the-way places demonstrates that they are out of range about 2% of the time.

For information on setting up these devices, see this page.

Flight Deck

It can be difficult to mount a GPS, a Vario, a compass, and a camera somewhere on your legs with straps. Instead, use a flight deck. It has various compartments for things like a camera, snacks, weapons, matches, first aid, etc. It mounts with straps to the webbing next to the karabiners on the harness. It is easy to take it on and off. Below is a photo of the Sol flight deck for $99. It is difficult to mount a GPS, a Vario, a compass, and a camera somewhere on your legs with straps. Instead, use a flight deck. It has various compartments for things like a camera, snacks, weapons, matches, first aid, etc. It mounts with straps to the webbing next to the karabiners on the harness. It is easy to take it on and off. Below is a photo of the Sol flight deck.

Radio harness

A radio harness is optional but has the advantage of securely attaching your radio to your person and protecting it. It also has a convenient pouch that can be used for storing extra batteries and a Garmin In Reach satellite communicator. A flight deck can be used to store batteries but you have to fuss with a zipper in flight which can take two hands. The radio pouch has a Velcro flap which is easy to open. Another advantage of the radio harness is that you will often find yourself on the ground without your harness and flight deck on and in need of radio communications. The radio harness makes it easy to safely and securely carry your radio at all times.

Other equipment

Things like a two-step speed bar, flight suit, gloves, catheters, etc. can be useful, depending on conditions and where/when you are flying.

Used gear

Used gliders can offer a significant savings but will not have the life of a new one because fabric and lines can decay with age and exposure to the sun. If you plan to fly more than 30 hours a year, new gear is a better value as you will not have to replace it before its useful life is up. However, some gliders have high quality fabric coatings that resist UV degradation for 10+ years. This is typical of the Ozone and APCO gliders. Glider lines rarely last more than 7 years and should be checked every two years.

It is important to remember that your life depends on the safety and condition of the gear you fly with. Used gear (other than from reputable dealers and schools) has unknown origin and usage. Do not buy used wings or reserves without having them inspected by factory authorized inspection centers. Sellers of such equipment should be happy to share the cost of an official inspection.

Gear size & weight

PG gear is so lightweight and compact that it can go as regular baggage on commercial jets. With some special lightweight models, your entire aircraft with instruments and safety equipment can fit in a small back pack that will fit in the overhead bin on a small plane.

![]()